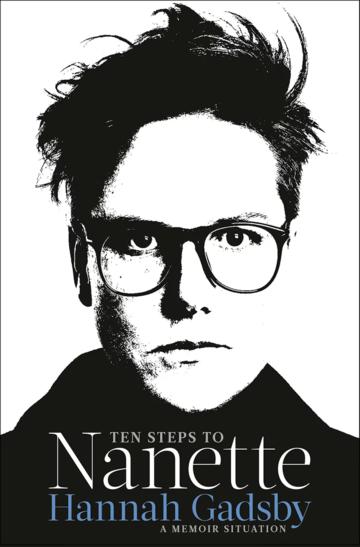

Ten Steps to Nanette by Hannah Gadsby

Ten Steps to Nanette by Hannah Gadsby

'Back then in the good old days, “lesbian” had a different meaning to what it does today – back then a lesbian was just any woman not laughing at a man' (cited on p.347)

So opines Hannah Gadsby in the Perth edit of Nanette. Though really, as she shows in Ten Steps to Nanette, she is a lesbian who laughs at (cis) men quite a lot, in a devastatingly funny way that never forgets gendered violence.

If you are a fan of Nanette (or like me think it was one of the greatest shows on earth), this book will help you to understand where Nanette came from and how Gadsby developed it both in the wider context of the virulent homophobia she experienced growing up in Tasmania and in the personal context of her own life (including her autism and ADHD, abuse and trauma, her family, and her studies). Ten Steps to Nanette explains some of the decisions Gadsby made as she developed her comedy. For example she relates that she decided to avoid discussing autism in Nanette, even though it’s a very autistic show (‘a flaunting of my atypical brain’, p.328):

My ASD was an easy drop; I knew that by bringing it into the conversation, everything I had to say about anything else would be measured against the mountains of misinformation that is built into most people’s misunderstanding of it (p.327).

At one point, Gadsby describes Nanette as ‘basically Eat Pray Love for autistic queer folk’ (p.355). Despite being a huge fan of Javier Bardem (Javier si por casualidad lees mi reseña, soy tu fan numero uno), I haven’t watched Eat Pray Love so I’m about to express a no doubt misguided opinion. However, the quotation on the back of Ten Steps is one of the most resonant lines from Nanette: ‘there is nothing stronger than a broken woman who has rebuilt herself’. Perhaps this is the kind of quotation that Gadsby has seen becoming meme-ified (p.355). But the quotation is also true and no doubt has been genuinely uplifting and helpful to many in Gadsby’s audience. Perhaps this meme-able truth is what Javier embodies in Eat Pray Love - I don’t know. But I do know that what I particularly loved in this book was Gadsby’s description of Nanette as ‘stand-up catharsis’ (p.22).

As all Nanette-lovers know, Hannah Gadsby is very good at structuring things, and Ten Steps to Nanette offers us a laugh of acknowledgement at a good ten-step structure from beginning to end. Gadsbury also expounds some of the thinking behind the structure of Nanette, notably:

The first half is crammed full of very solid punch lines…I needed my audience to trust me because I needed my audience to feel safe, and I needed my audience to feel safe so I could take that safety away and not give it back. Why? Because that is the shape of trauma (p.22)

It’s perhaps then, particularly ironic that, as she relates in her book, Gadsby initially spent ages ordering Nanette on a series of cue cards, then dropped all the carefully-ordered cards before her first performance and had to pick them at random out of a basket. It’s perhaps, then, particularly infuriating that when she participated in a documentary about Western Art, her interventions, ideas, and anger were stage-managed away in favour of a blander more muted structure:

I had wanted to keep in the film all the tense exchanges I’d had with all the white men. I thought it was interesting that they chose to speak over the top of me so they could make dumb and sexist statements, but I was told that it would make me look bad, because I came across as angry. It didn’t matter to me that I came across as angry. I had no problem coming across as angry. But apparently I don’t get to choose how I look, which I guess, in a documentary about Western art, is pretty on-brand (p.303)

As Gadsby cautions readers at the beginning, we cannot – and should not – use the book to play detective about her life, thinking that we’ve totally cracked her code. The same goes for Nanette: though I understood a whole lot more about Gadsby’s show from reading this book, Gadsby also preserves the mystique around her craft. She provides various interesting- and to me baffling – insights into her process, like diagrams she drew of Nanette and (in step 9) a description of the show using the mixed metaphor of a woven layer cake.

Gadsby mixes this with some anecdotes that, well, made me chuckle. For instance, she tells a funny story about a dog, which I would like to share with you before I go. Complaining about an unsupportive moment with her mother, she writes, ‘Mum would sometimes stray into the badlands of active discouragement, like the time I declared, when I was about eight years old, that I wanted to be a dog when I grew up, and she counselled me to consider a more practical vocation, like not being so bloody stupid’ (p.29).

I am sure that Gadsby’s reflections on life as a neurodivergent girl will resonate with many readers:

Despite my woeful results, I did manage to learn one incredibly valuable lesson in my final year at school, and that was just how easy it was for a girl like me to slip through the cracks unnoticed. And because I am who I am, that was neither good nor bad; it was just a fact (p.151)

I am thankful that Gadsby did not completely slip through the cracks, that today she is asking us to take notice: notice of her, and of the issues she raises about neurodivergence and queerness.

Dr. Laura Seymour is a fixed-term stipendiary lecturer in English at St Anne's. She researches neurodiversity in early modern European writing, and neurodiversity-inclusive pedagogy. She is currently finishing Shakespeare and Neurodiversity (Cambridge University Press, 2024), a guide to teaching Shakespeare in a neurodiversity-inclusive way. As an autistic worker and researcher, she is particularly interested in ableism in academia, and how it intersects with factors like race, class, and job precarity.